Menu

The Freudian revolution was inaugurated by the unprecedented discovery of the Symptom of the hysteric with wars telling the truth of the patient that seeks to be heard rather than observed. The symptom has a definite advantage in not being examined like some strange object that causes suffering, « bilderschrift » according to Freud. In English he would doubtless have used the word « hieroglyph » or perhaps more literally, « image-writing ».1

When we realize that fifty years on, the medical profession along with Leriche would declare that health lay in life in the silence of the organs, and that it was therefore desirable to reduce the noise of the Symptom to silence, one can appreciate the revolutionary character of the Freudian perspective.2

Let us recall what Freud provoked Dora’s cough to say : « I am the daughter of Papa. I have a cough like his. He has caused my illness just as he caused Mama’s illness. It is from him that I inherited these bad feelings which are punished by illness ».3

As you know this aspect of the message was not the only aspect of the Symptom. To Freud it was also the indication of an original trauma, as well as disguised satisfaction with repressed impulses. In other words, it was a form of compromise.4

Most post-Freudians perceive this last aspect to more significant than the first one. Many psychoanalysts have become deaf to messages encysted in the wait for deciphering at the heart of the Symptom.

Lacan revealed this Freudian intuition in 1952 in his «Discourse at Rome». The Symptom is a message addressed to the other, an enigma searching to be deciphered, a hieroglyph seeking a subject capable of understanding and interpreting.5

This is far from evident as the Symptom speaks even to those who cannot, or do not wish to listen. And it doesn’t tell all, rather it conceals its real significance even towards those who are willing to listen.6 The messenger himself ignores the existence of the author, as well as the person to whom the message is addressed.7 In other words, the Symptom «moves towards recognition of desire, but it is illegible». What is more, « it moves towards the recognition of desire, but the desire is excluded, repressed ».8

An indication of a repressed signifier, while at the same time, a signifier (from signify-the trauma) that represents the subject for another signifier,9 the Symptom in this case is relevant to the teachings of Lacan in the area of the Symbolic. We can see here how it differs radically from a medical Symptom which is a sign of an organic Dysfunction.

In the course of his research, Lacan became more and more interested in the Real and discovered first the topology, and then, the Borromean knot.

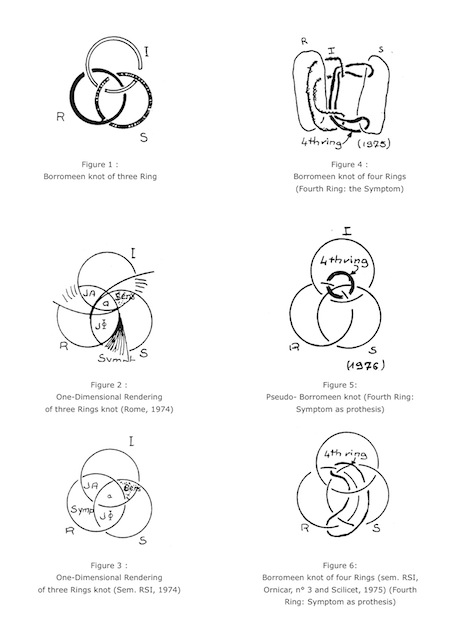

We well know the definition of the latter: at least three strands knotted together in such a way that if one should break, no matter which one, all the others would come undone (Fig. 1). This type of knotting is precisely that which binds together the Real, the Imaginary, and the Symbolic of which Lacan spoke since 1952.10 The Borromean knot of three rings seemed to him to be the perfect form to describe the structure of the « parlêtre ». (n.b.)

Where is the Symptom situated in this structure ?

That is the question that Lacan asked himself in his second « Discourse at Rome » (1974).11 Working on the one-dimensional rendering of the Borromean knot of three rings, he situated the Symptom principally in the Symbolic, partially in the Imaginary, and marginally in the Real (Fig. 2).

There is nothing surprising in this, in that as we have just said, the Symptom represents the subject for another signifier, and it is laden with meaning. In his second « Discourse at Rome » Lacan added a new dimension to the Symptom : its relationship with the Real. « I call Symptom », he said, « that which comes from the Real » and, « the meaning of the Symptom is the Real ».

In the months that followed, Lacan was to confirm this relationship of the Symptom with the Real. As this can be visualized in the figure 3 established at the RSI Seminar,12 he situated the symptom this time in the Real out of the field of the Imaginary and the Symbolic . He said of this figure, « The Symptom is the effect of the Symbolic on the Real ».13 During one of his conferences at American universities in 1975, he added that the Symptom was, « that which people have that is most real » and also, « the mark of human reality ».14 Let us further note that in 1975 Lacan defined the Symptom as, «the means by which each rejoices in the unconscious as the unconscious determines it».15

All this is not without consequence in the practice of interpretation, on the idea one has of healing, and on the representation we have as to the completion of the cure.

Indeed, if one considers the Symptom as coming from the Real into the Symbolic, one must agree that it has little relevance in the Imaginary and the universe of significations. In figure 2, one can observe the development of the zone of Symptoms that would result from any intervention that would give significance in the zone of the Imaginary. The expression « to nourish the Symptom by significance » precisely describes the effect of maintenance and the development of the Symptom that often results from such intervention.

To say that the Symptom is the effect of the Symbolic in the Real, is to state even more radically that the Symptom is beyond the reach of the Imaginary and thus, out of reach of significations (Fig. 3).

This implies that the truth of the subject encysted in the Symptom is a truth that has nothing to do with signification; that the message to be deciphered is non-sense; that the appeal that the Symptom carries is constituted of signifiers of no real meaning.

One can easily see that in such conditions interpretation can no longer be what it was at the beginning of the psychoanalytic experience : a simple revelation of hidden significations.

Lacan did not stop at this « ex-istence » of the Symptom outside the boundaries of the Imaginary. In his conferences and discussions at American universities,16 his nodal forms re-knotted the ring of the Symptom with that of the Imaginary, the Real, and the Symbolic (Fig. 4). Must not one conclude that none of these dimensions should be neglected if one is to adequately understand the Symptom ?

Moreover, if the Symptom is « the mark of human reality» and «the means by which each rejoices in the unconscious », it is evident that the cure cannot simply consist of eradicating the Symptom.

This eradication of the Symptom becomes even more impossible as Lacan began to consider the Symptom more and more as a manifestation of structure : an effect of the impossibility of sexual rapport.

During the process of Borromean knotting, failure stalks those who would try. The rupture of a ring brings with it, by definition, the dispersion of the others. Failure, a mistake in the crossing of the rings, brings with it diverse consequences according to the strands that are implicated in these mistakes. One ring can weaken the other two.

One emphasizes the catastrophic character of such errors in the knotting when they affect the structure of a subject. What is a subject, for example, deprived of the Imaginary ? To suppose that exists, what then is it to live in a universe full of signifiers without any signification, in a phallic delight that is incomplete in the delight of any meaning for the subject or for the other, and in an uninterrupted confrontation with the Real stripped of imagination.

Within the logic of the Borromean knot, it is possible to remedy such a dis-association of the three rings. This nodal logic allows one to imagine a prothesis, the possibility of a prothesis that can be clinically observed. Indeed it was through his work on Joyce that Lacan came to the conclusion that prothetical function was possible for certain Symptoms.

Thus, in the case of an error in knotting situated at one of the crossings of the Real and the Symbolic, to compensate for the shift in the ring of the Imaginary, it is nodally possible to re-knot the Real and the Symbolic by means of a fourth ring (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Lacan situated the Sinthome at this point. The spelling deliberately differentiates the Sinthome from the Symptom according to the ancient use of the word. Until now, we have distinguished the Symptoms by their function as protheses in re-knotting the Real, the Imaginary, and the Symbolic that risk becoming un-ties as the result of a poor original knot.17 Lacan emphasizes that this spelling is more appropriate because it includes within the signifier itself another signifier that is directly associated : that of an error, « sin » in the mother tongue of Joyce.

The writings of Joyce have, for Lacan, a sinthomatic value as well as fulfilling the role of a prothesis. This sinthomatic activity of the writer allows him a substitute ego by which, in addition, the writer makes a name for himself.

One must insist here that this Sinthome is not without rapport to the « Name-of-the-Father ». It’s not the family name but a function described by Freud as the paternal function and Lacan says that it’s also what religious call Gad. ; the failure of the metaphor from which it originates in some way as a substitute.

Lacan elaborates on this theory of the Sinthome using an example of psychosis.

In this same seminar on the Sinthome, he generalized its structural function as the fourth ring and noted the structure of the « parlêtre » from this new Borromean knot composed, in the beginning, of four rings : the Real, the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Sinthome. One observes the difference from the preceding knot that was not Borromean. In his commentary, Lacan indicates that the Sinthome is equal to the Œdipal complex.18 Even before this, he suggested that the Symptom could have the same function of knotting as that of the « Name-of-the-Father ».19

From month to month, Lacan oscillated in his response to the question of whether one should consider the Sinthome to be a component structurally necessary for a normal or neurotic structure. Nodally, the question is double-barrelled and can be formulated as follows : First, is the fourth ring of the Sinthome present in all of the structure (normal, neurotic, and psychotic) ? Second, in the affirmative, is this knot of four strands Borromean (Fig. 5) or not ? (Fig. 6)

If Lacan hesitated to give his response, a general tendency began nonetheless to appear in his teachings; the fourth ring of the Sinthome is necessary, it is part of the structure. One finds, for example, the following affirmation: «the ex-istence of the Symptom is implicated by its very position, by the tie of the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real».20 He goes on to state, «without this fourth ring there is no tie between the Imaginary, the Real, and the Symbolic» : that is, a perversion.21 Later, speaking about the completion of the cure and referring to the original repression that can never be cancelled, he said, «There is no radical reduction of the fourth term».22

At the same time, he sensibly enlarged the concept of the Sinthome, and this is very important.

Far from reserving its prothetic function for sleep disorders and psychic disturbances, he saw it as part of diverse Sinthomes. Lacan thus evoked the role of art for certain artists, mathematics for certain mathematicians, God for certain believers, the psychoanalyst for certain patients, and last, their lover or loved ones for certain lovers.

If the Sinthome is an integral part of the structure, what is one to do with it during the cure and what does it become upon completion of the cure?

At the beginning of his teaching career, Lacan, faithful to the Freudian recommendation to never aim for «the short-term cure», let go of the aphorism the waited for healing «de surcroit». He provoked strong reactions among those who, insensitive to the fact that «de surcroit» meant «as natural and necessary supplement», paradoxically understood a disdain for the cure seen as accessory. During his seminar on Anxiety (1962), he stated, «It is certain that our justification, as is our desire, is to improve the position of the subject».23 In the directory of the Freudian School in Paris (1975) one can read the following passage signed by Lacan: «Psychoanalysis has, however, distinguished itself by allowing access to the cure in its own field; that is, returning the meaning to Symptoms, making place for the desire that they mask, and rectifying through an exemplary mode the comprehension of a privileged relationship …» 24 Again he evoked the question of the cure in the United States but, this time, in terms of comfort : «They (the neurotic) live a difficult life and we try to alleviate their discomfort»… «An analysis need not be pushed too far. When the patient believes that he is happy to be alive, it is far enough».25 Charles Melman took up this same question of happiness later and said, « The analytic position cannot neglect happiness, but other than questioning what happens when it becomes an imperative, it cannot determine it to be, without risk of prejudice, the ultimate goal on its horizon ».26 Lastly, in 1978, during a conference on the transmission of psycho-analysis, Lacan invited the participants to question the processes involved in the psychoanalytic cure limited to the unique medium of the spoken word : « How is it that through the operation of the signifier, there are people who are cured ? Freud pointed out that not only must psychoanalysts desire to cure … but certain psychoanalysts among them were also cured of their own neuroses, their own perversions during the process. How is this possible » ? In his conclusion, he again confronted the question of the disappearance of the Symptom by describing it as the sign that the analyst had not missed his goal. But, at the same time, he evoked the Sinthome as that which did not disappear, as that which remains of the sexual relationship as an unsinthomatic relationship. Once again, it appears that one must differentiate, along with Lacan, those Symptoms that one has a right to expect to disappear in the course of an analysis (Lacan points out that «ptoma» means to fall) and the Sinthome of each individual which holds together the Real, the Imaginary, and the Symbolic.27

Contrary to that which sometimes seems likely, one is perfectly within one’s right to expect that in the course of a psychoanalytic cure, the Symptoms will disappear.

As for the Sinthomes, the nodal theorization invites caution, given their prothetic function. One can never eliminate, without grave consequences, the use of the Sinthome (ie : after a surgical intervention, or by a forced separation the object of love or desire, or even by a savage interpretation-the more destructive, the more exact).

As to the future of the Sinthome at the end of a cure, one must conclude that if, as Lacan affirms, one cannot hope for «any radical reduction of the fourth term» one can, however, hope for a partial reduction or shifting of a painful Sinthome to the advantage of another, source of less pain, and, why not, perhaps a source of pleasure. The experience of the cure teaches that if pleasure in suffering exists, it is often possible, provoking much less pain, to expect more and more pleasure.